January 14th

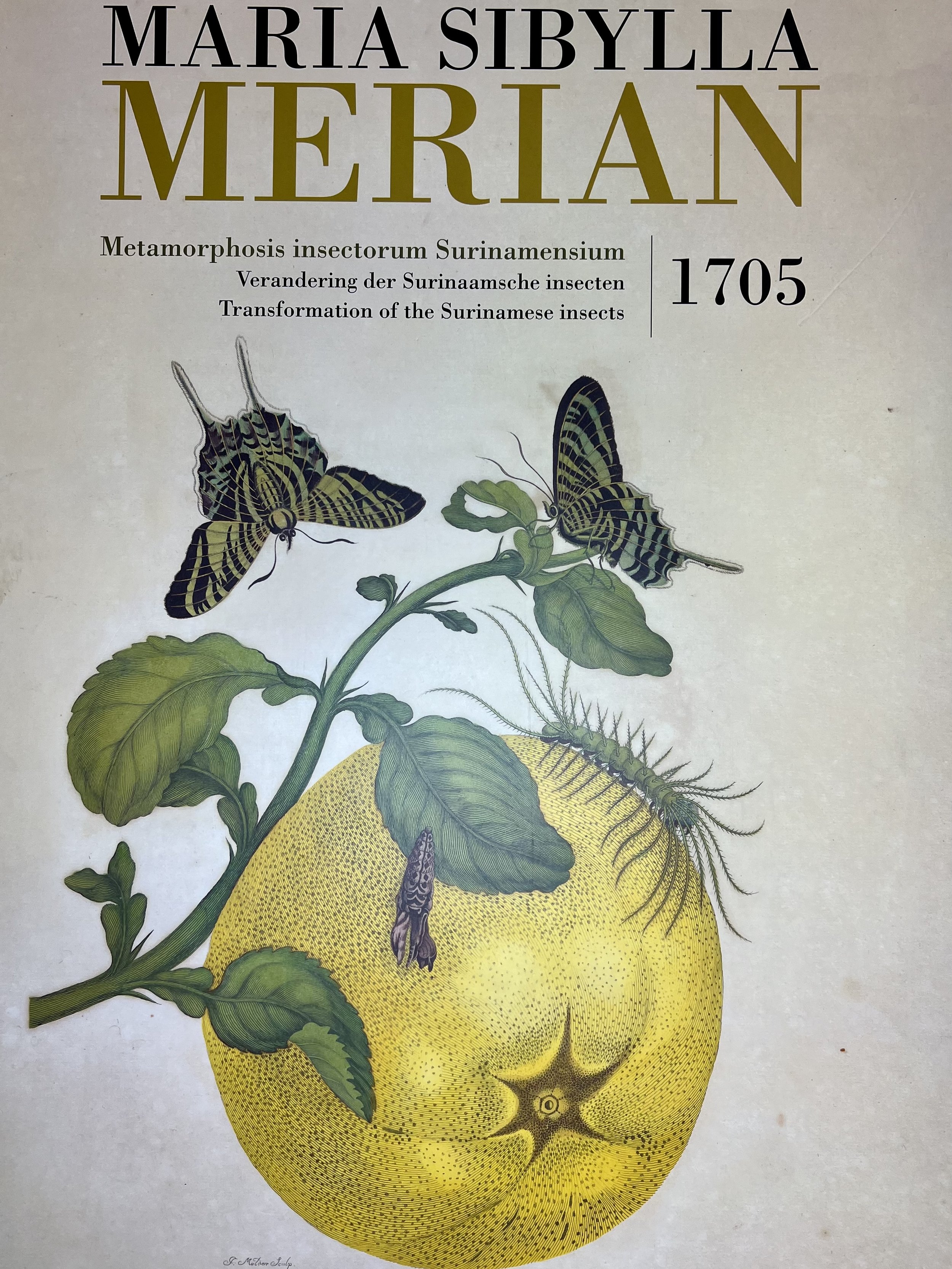

Today, as I immerse myself deeper into the world of ecological restoration and sustainability, I find myself fueled by an overwhelming sense of purpose. My Climate-Smart Urban Landscape project has truly become a labor of love, growing more meaningful with every leaf gathered. As I collect bags of native Oak leaves from curbs, I'm not just gathering leaves—I'm cradling potential life, the eggs, pupae, larvae, and chrysalises that might be nestled within. Astonishingly, Oak trees are home to over 900 species of caterpillars. These caterpillars serve as a crucial food source for many songbirds and their young across North America. By saving these leaves, I am inadvertently contributing to the survival of these beautiful creatures.

The interconnected benefits of these efforts are profound. First, by fostering biodiversity, I help ensure diverse species can thrive. Second, as the leaves decompose, they transform into a rich, nourishing substance that revitalizes our depleted soil, forming the very backbone of our food network. Third, these leaves provide essential shelter from harsh weather, acting as a protective barrier against heavy rains and cold temperatures and safeguarding the tiny creatures that rely on them to survive.

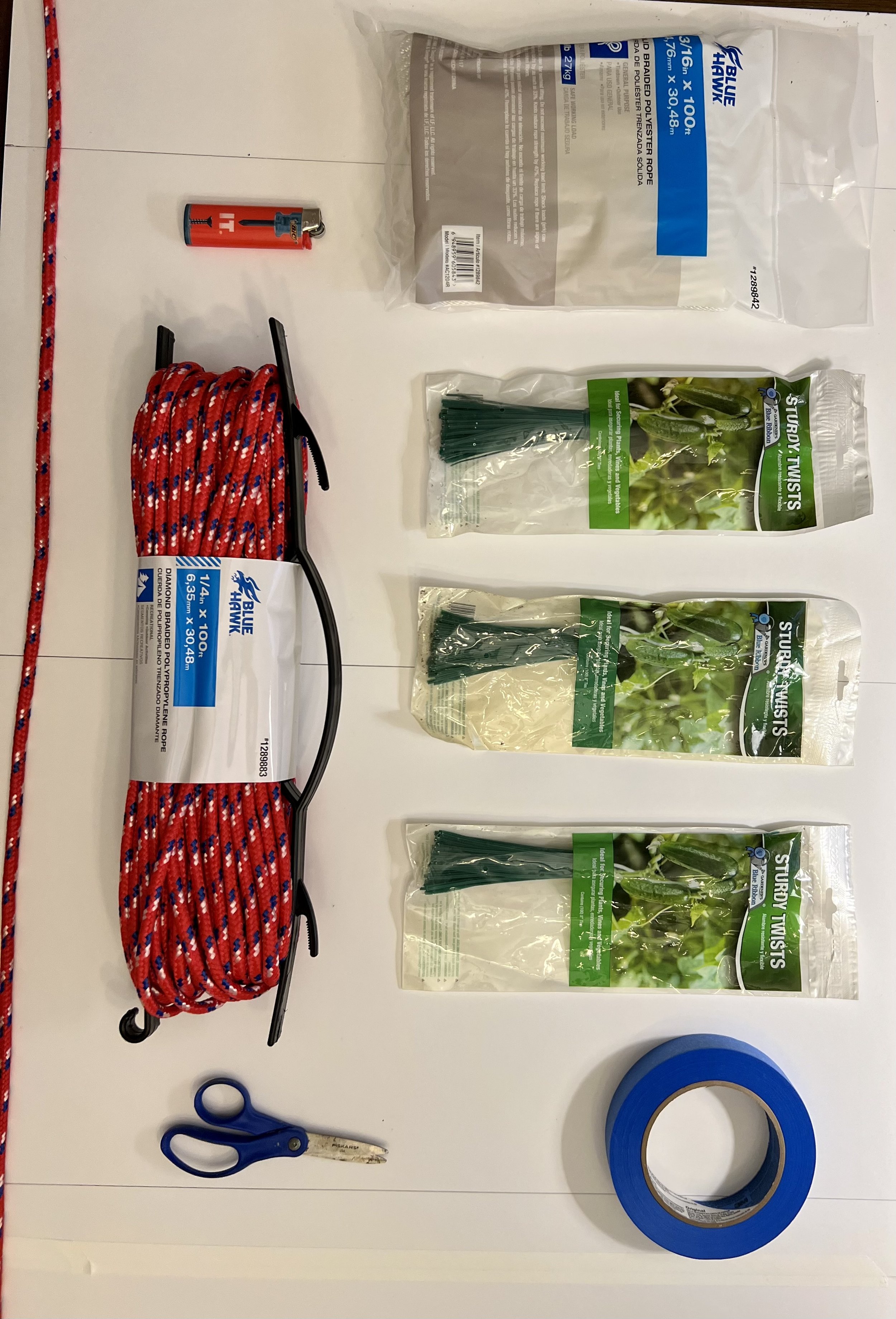

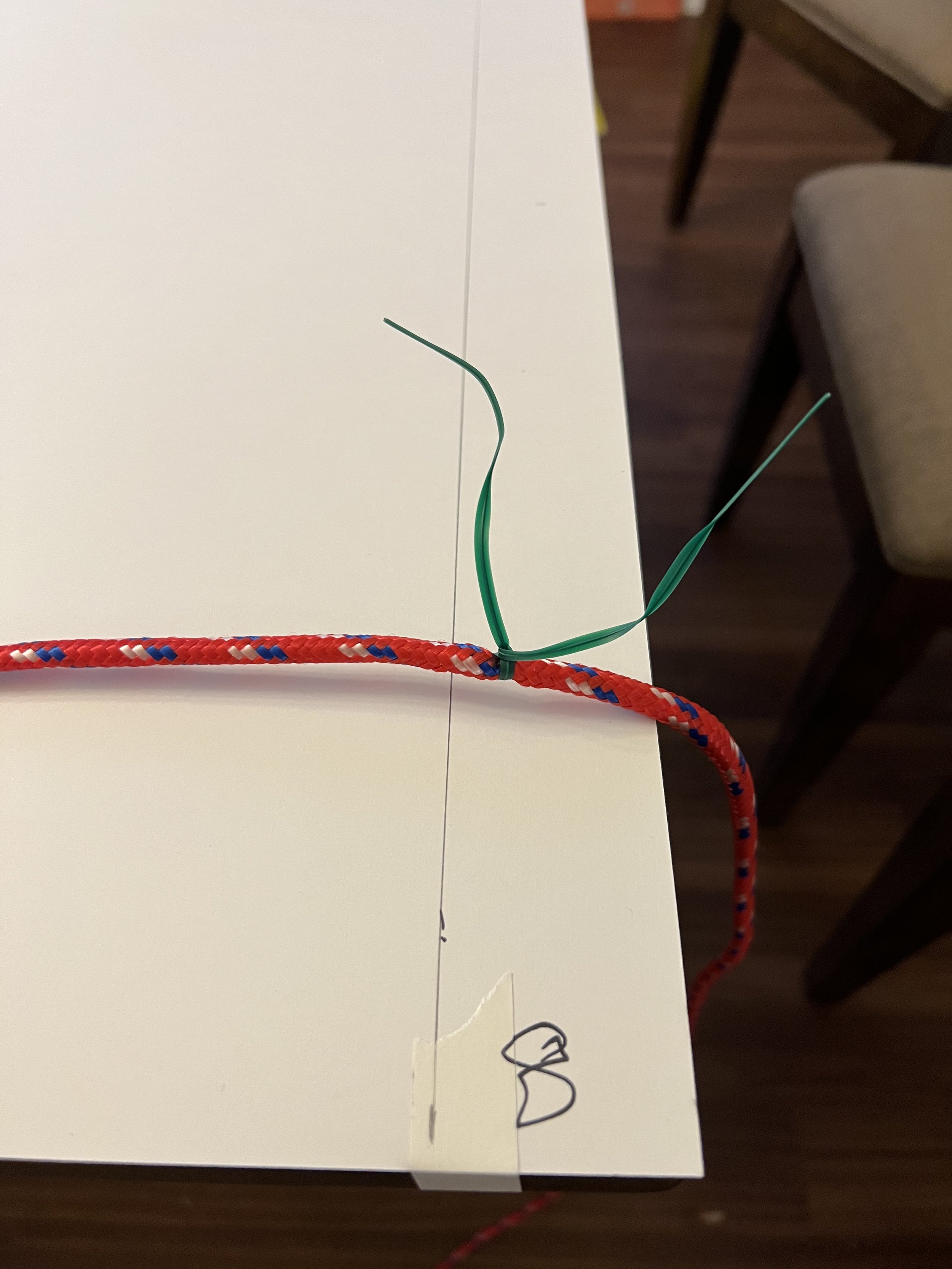

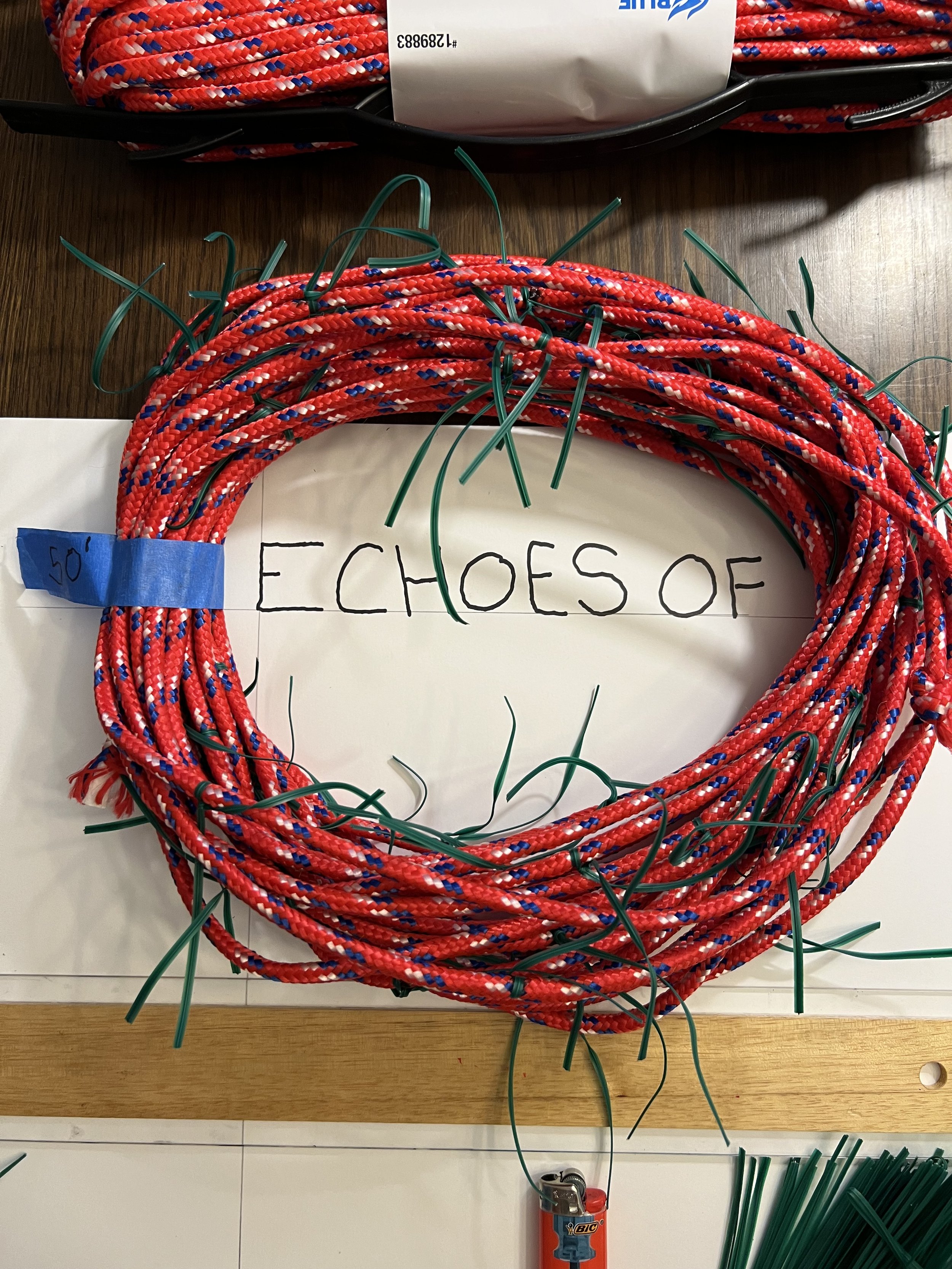

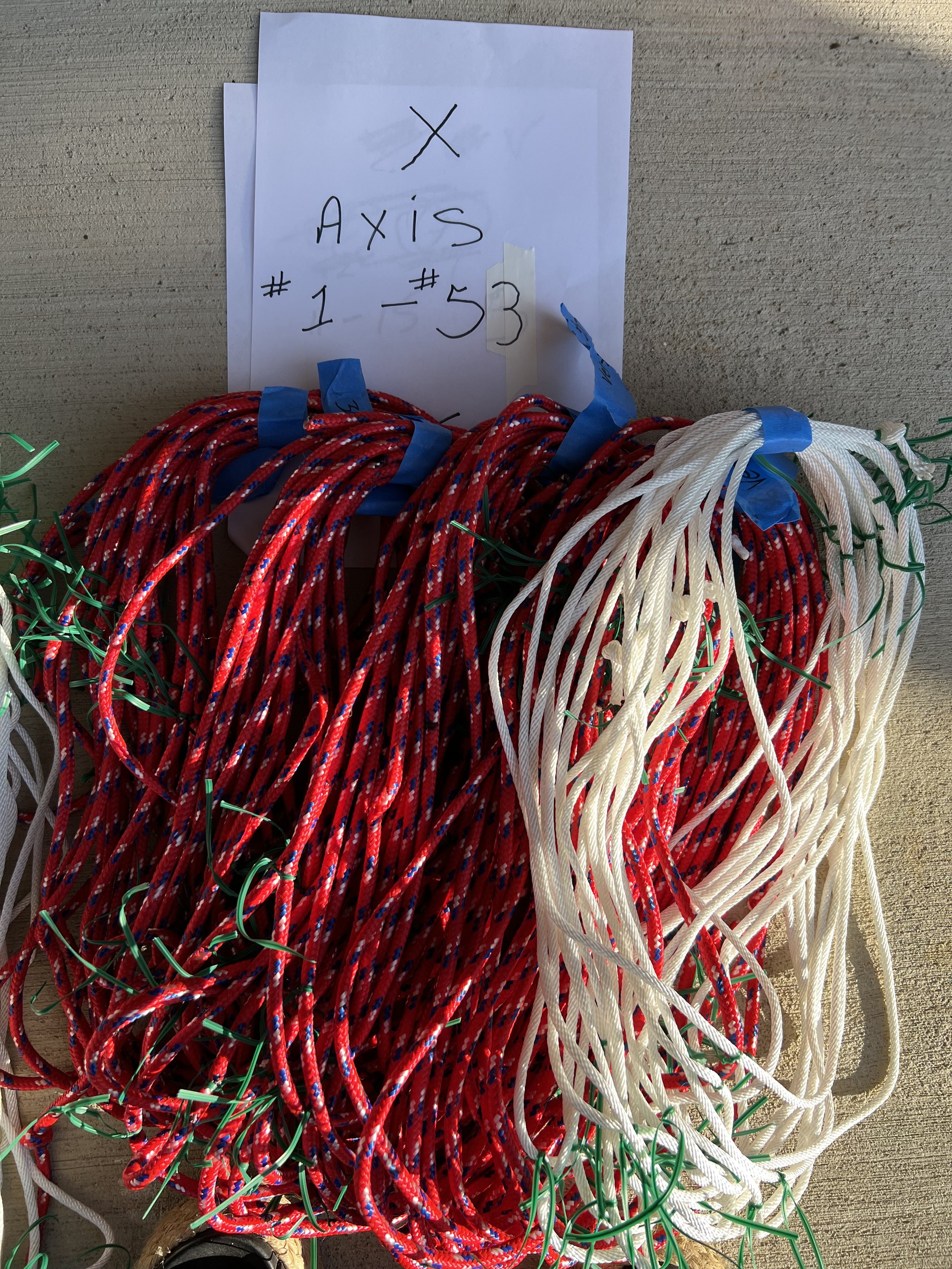

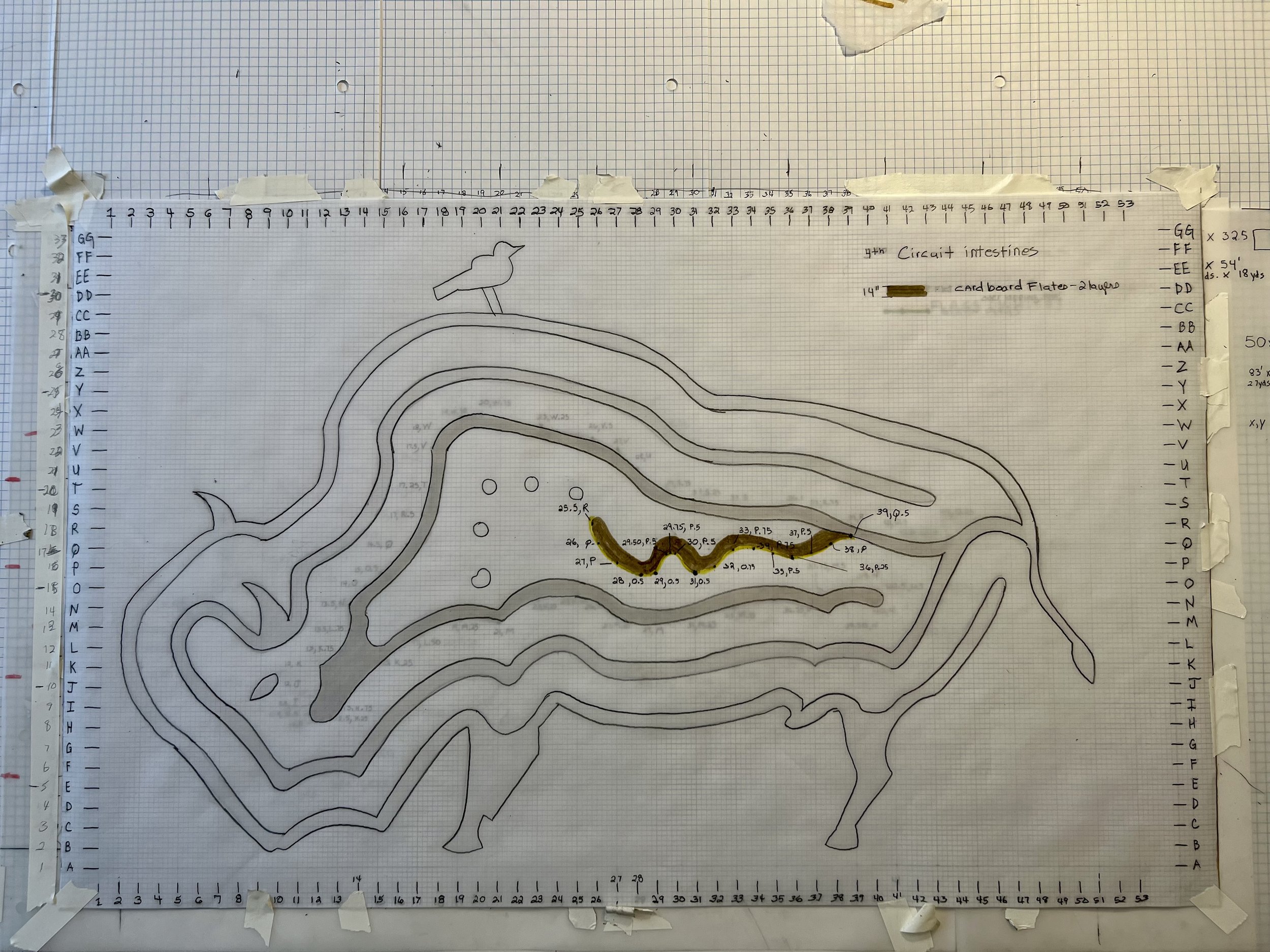

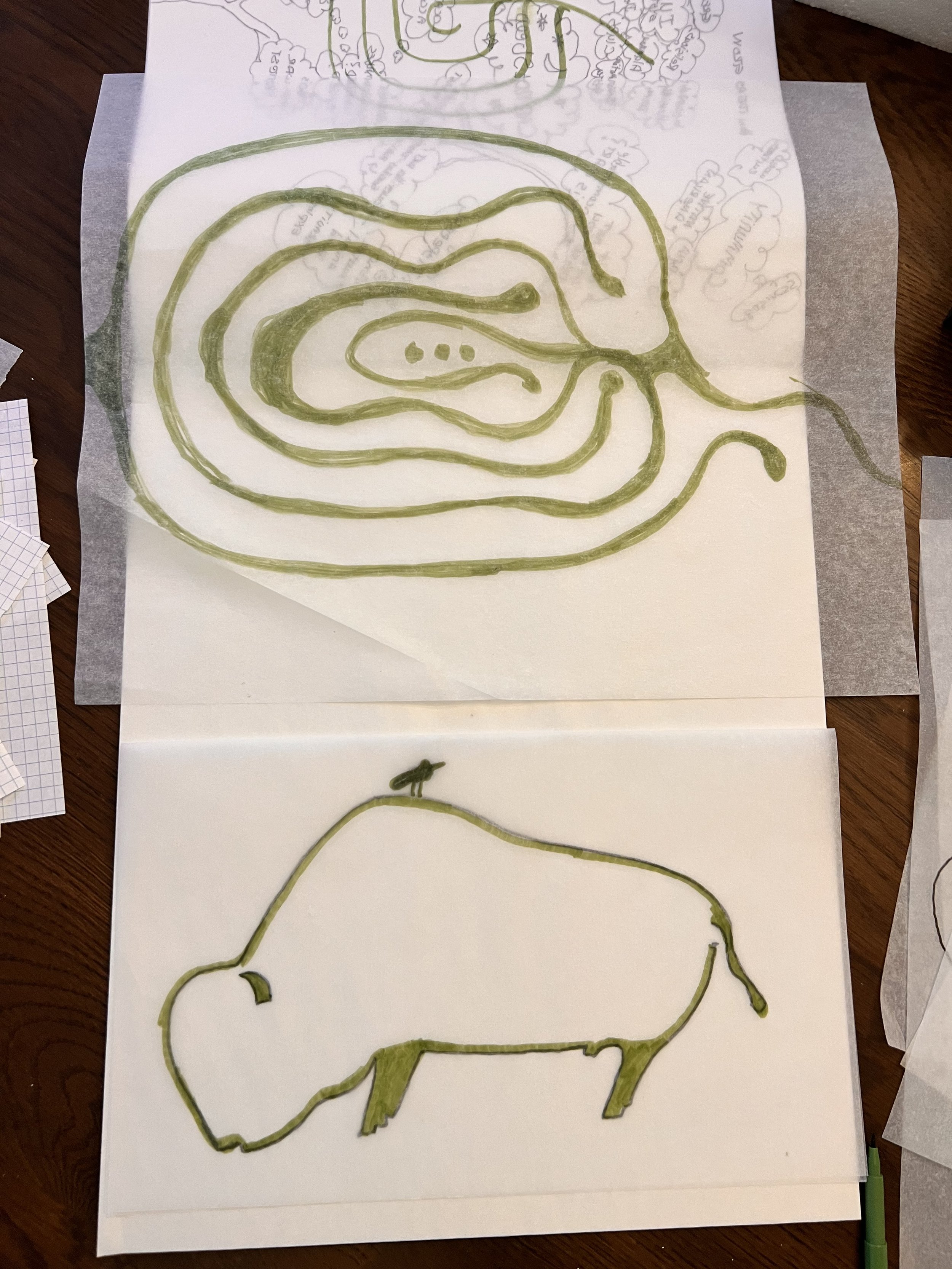

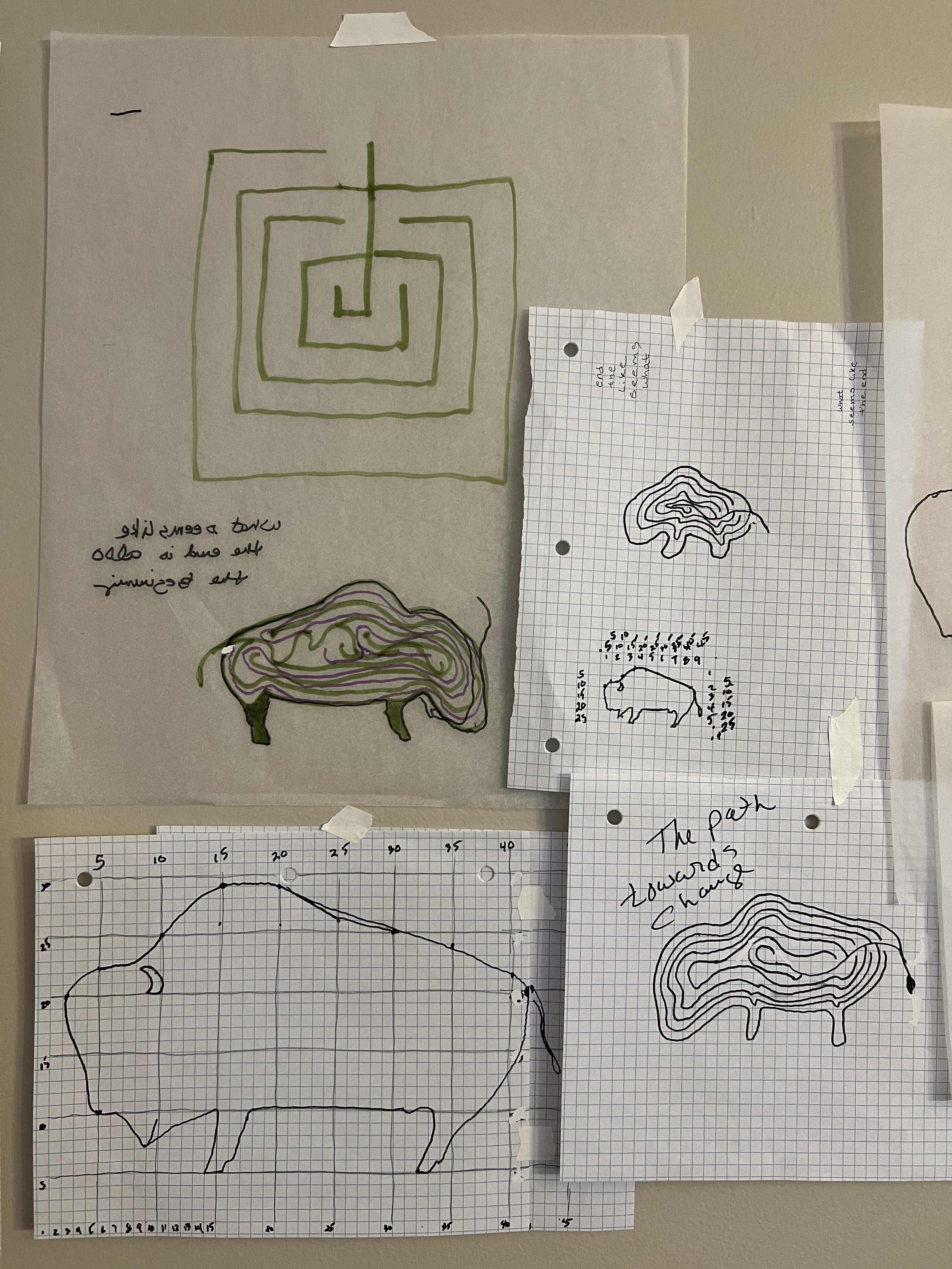

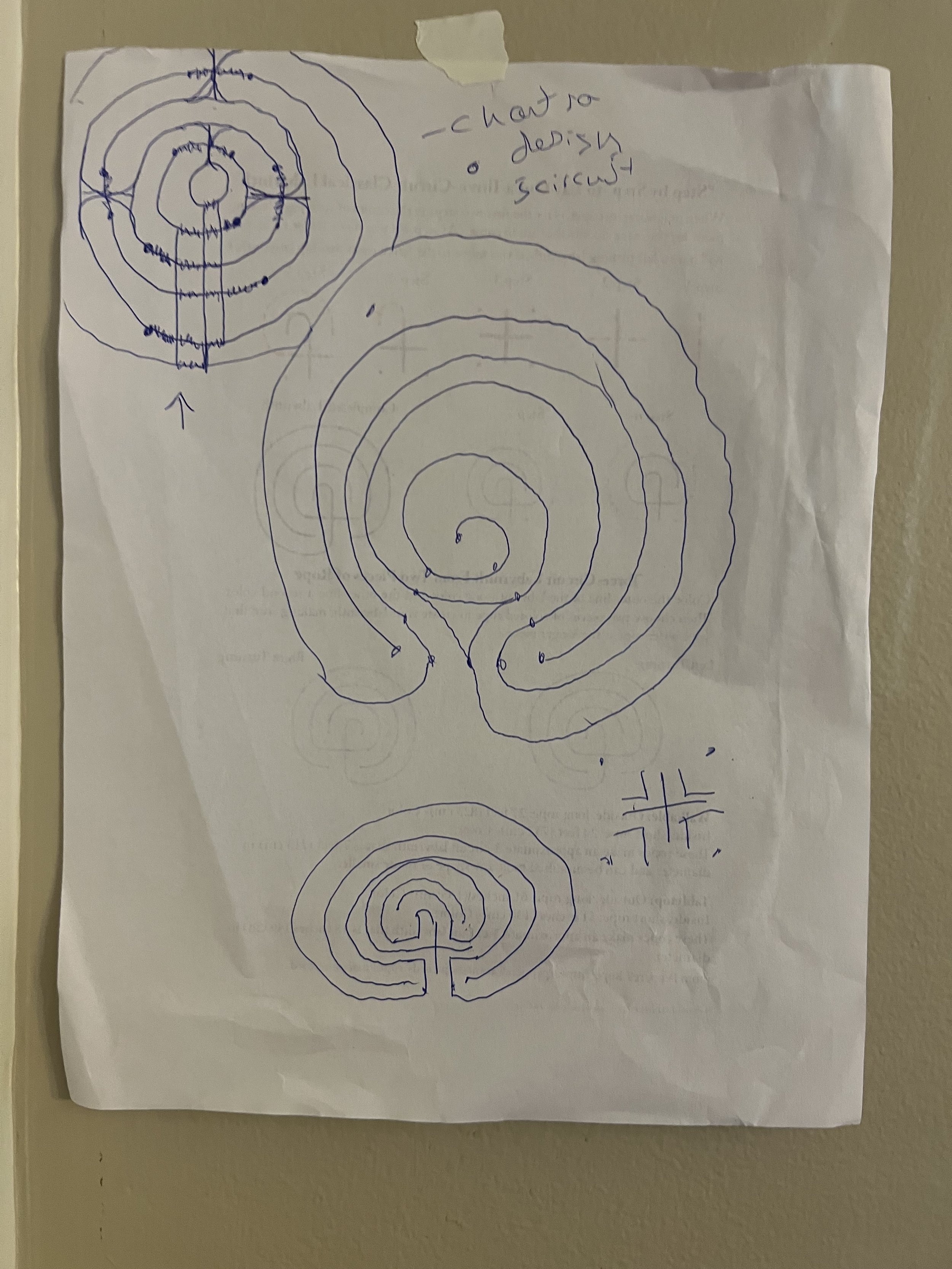

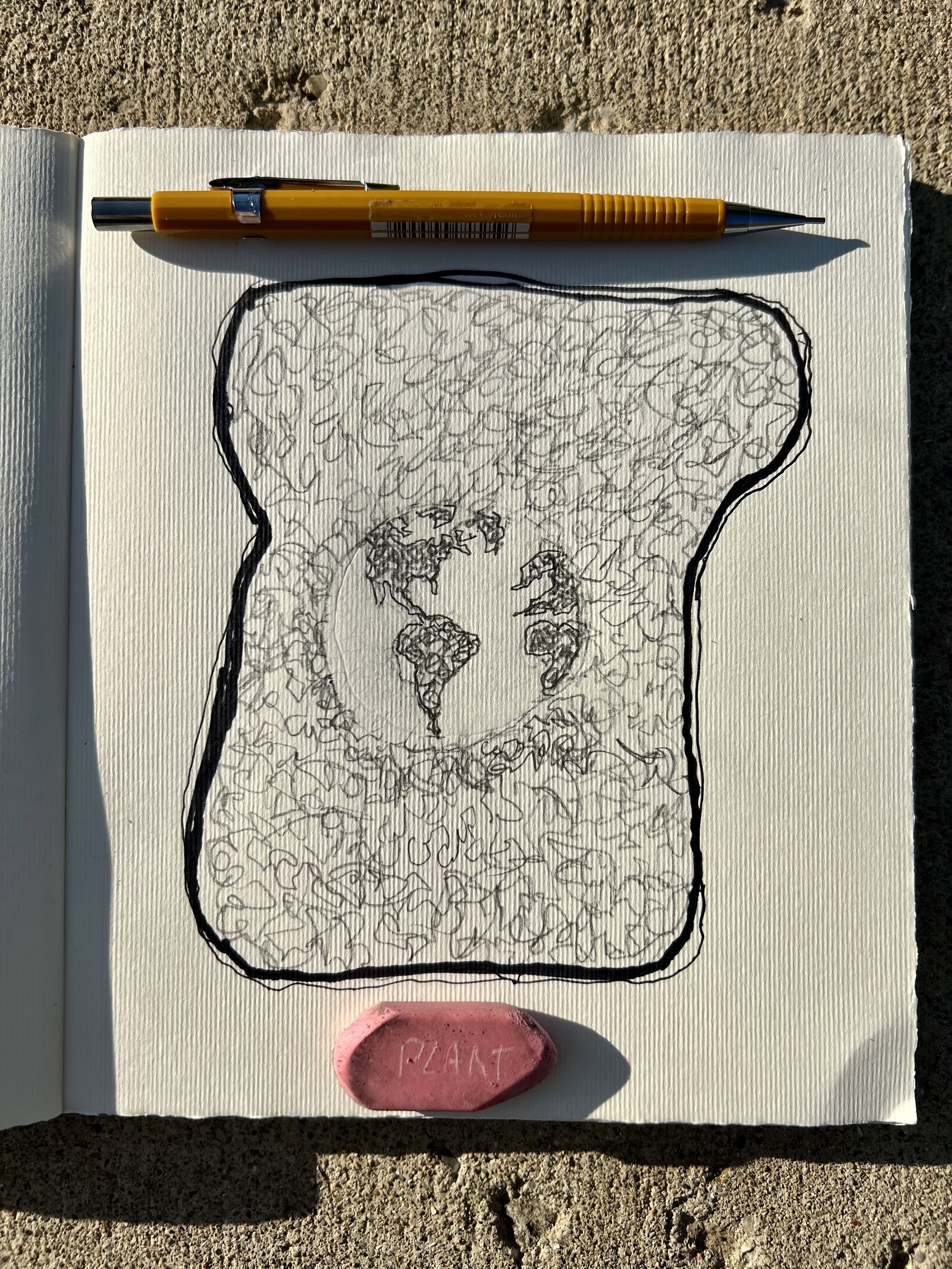

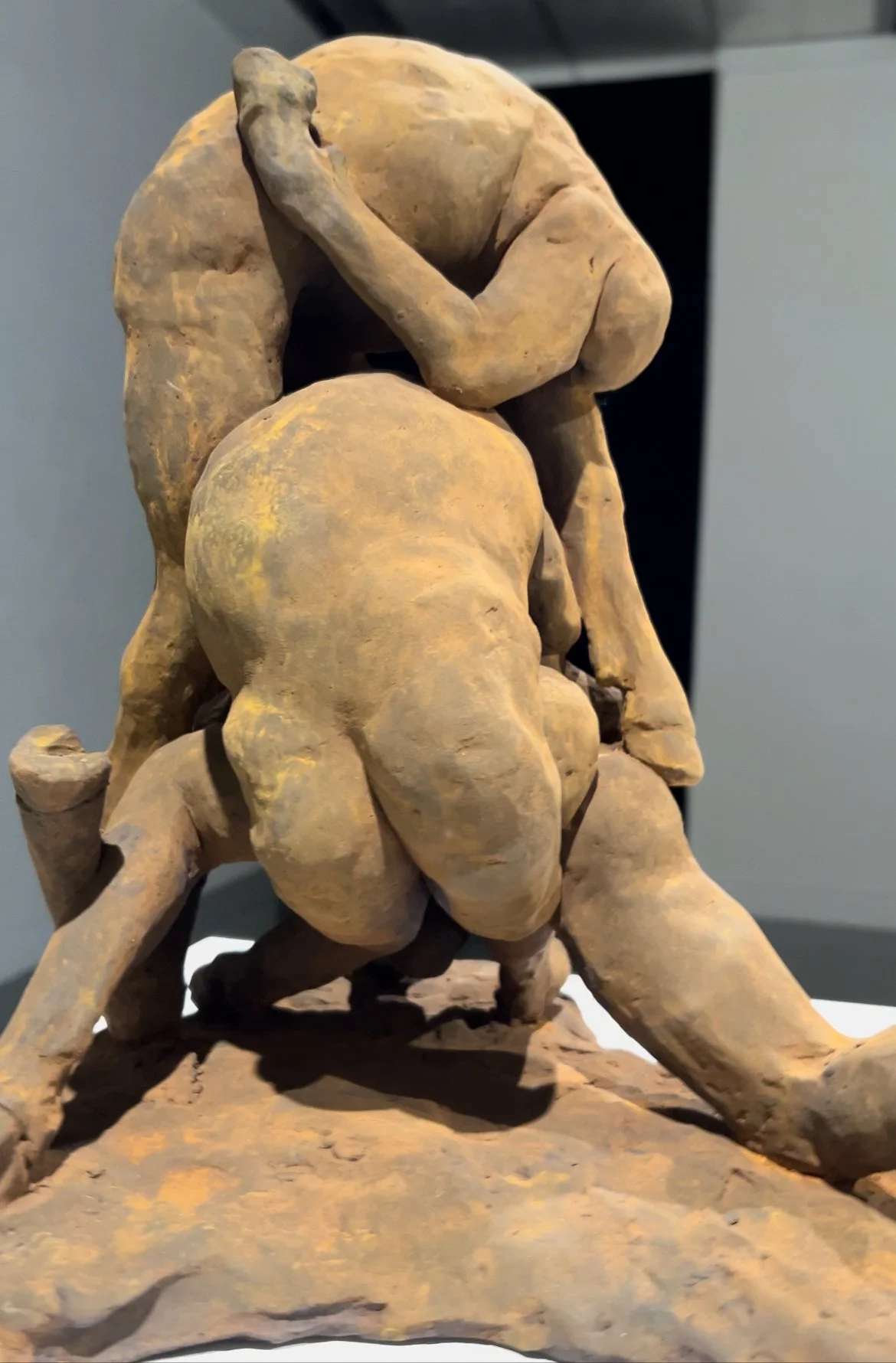

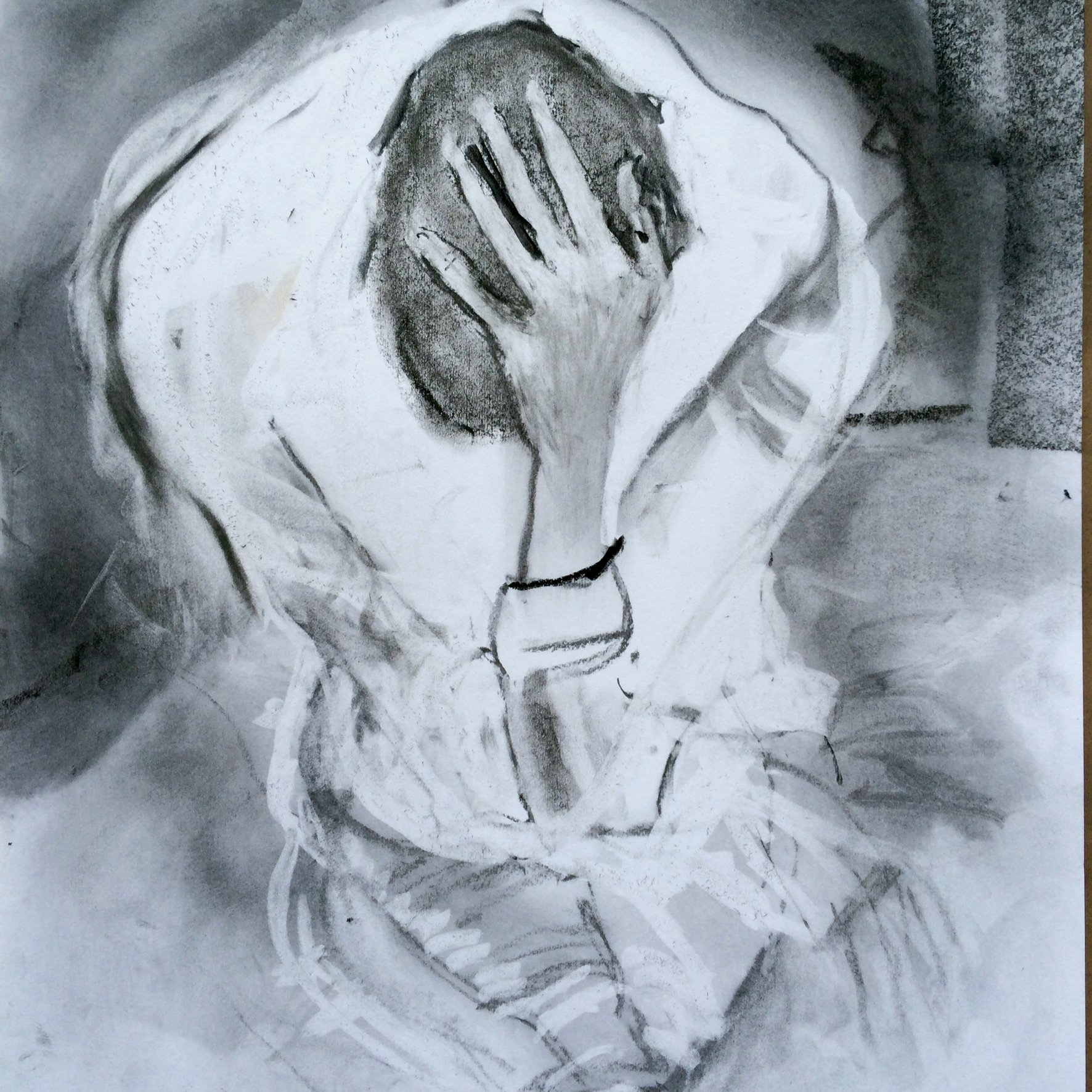

My inspiration stems from personal experiences and a deep sense of environmental stewardship. Through "La Mancha’s Sequel," my urban landscape project, I aspire to blend art, architecture, and environmental literature in a way that leaves a meaningful impact. My goal is to transform the local community here in Houston and ignite a larger appreciation for ecological interconnectedness. By sharing this journey, I hope to inspire others to commit to regenerative practices within urban environments.

With every leaf collected and every small step taken, I am moving toward a more harmonious world. This journey reminds me that each of us holds the power to make a difference in our neighborhoods, communities, and beyond. Together, we can create a future where sustainability and biodiversity thrive hand in hand.

#rain #soil #abstractexpressionism #houstonart #ecoart #socialsculpture #cindeeklementart #art #texasart #sculpture #contemporaryart #modernart #regenerativeart #sequel #acreshomes #foodnetwork #foodchain #regeneration #regenerativeart #artandscience #agriculture #agriart #foodnetwork #foodweb