Symbiosis Celebration

social sculpture

—from Chemical Plants to Native Plants—

Native Wildflowers, Food, Art, Music and Migration

Fall color tourism contributes $1 billion per year to North Carolina. Houston has fall and spring color migration; we can cultivate them into tourism and build soil health.

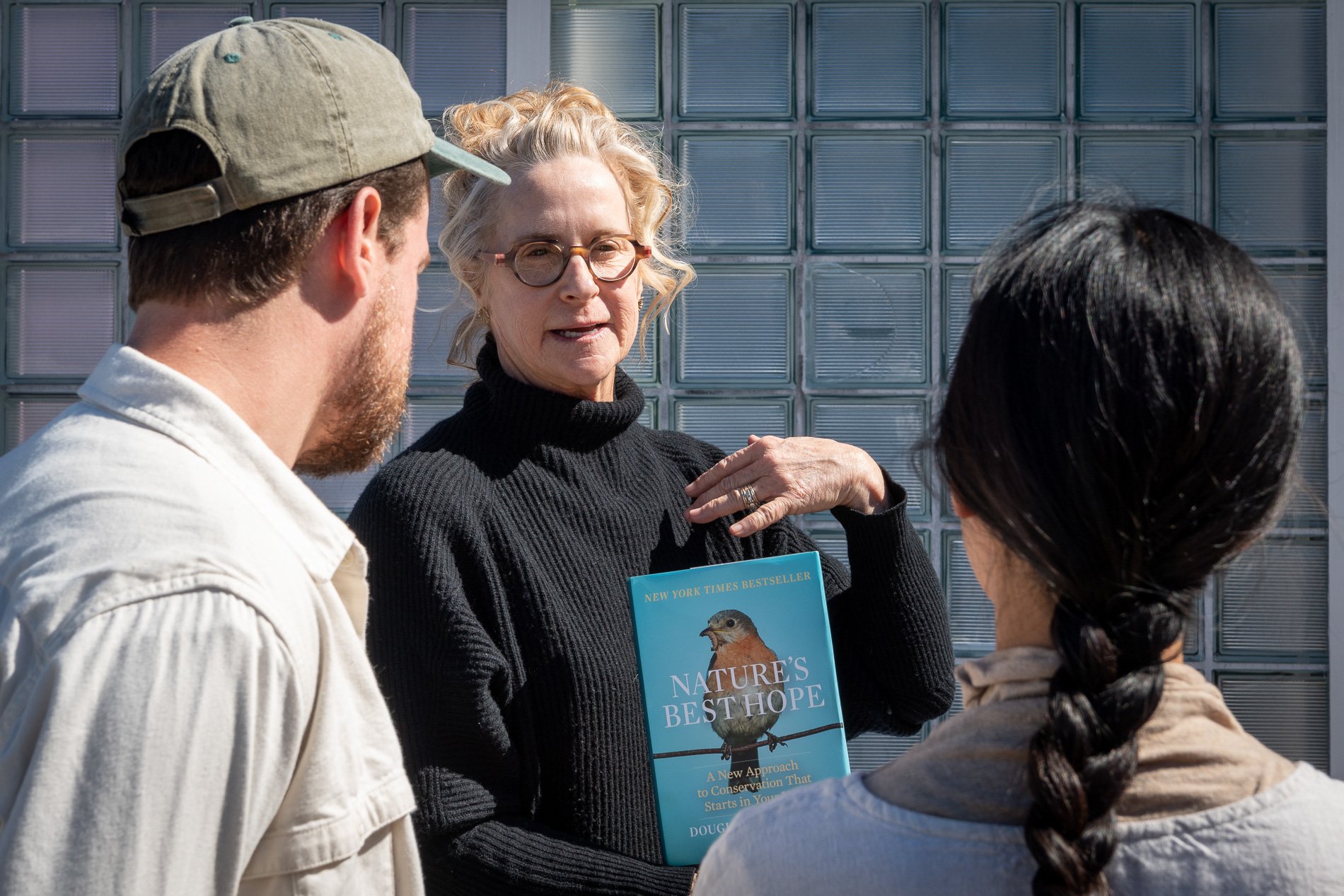

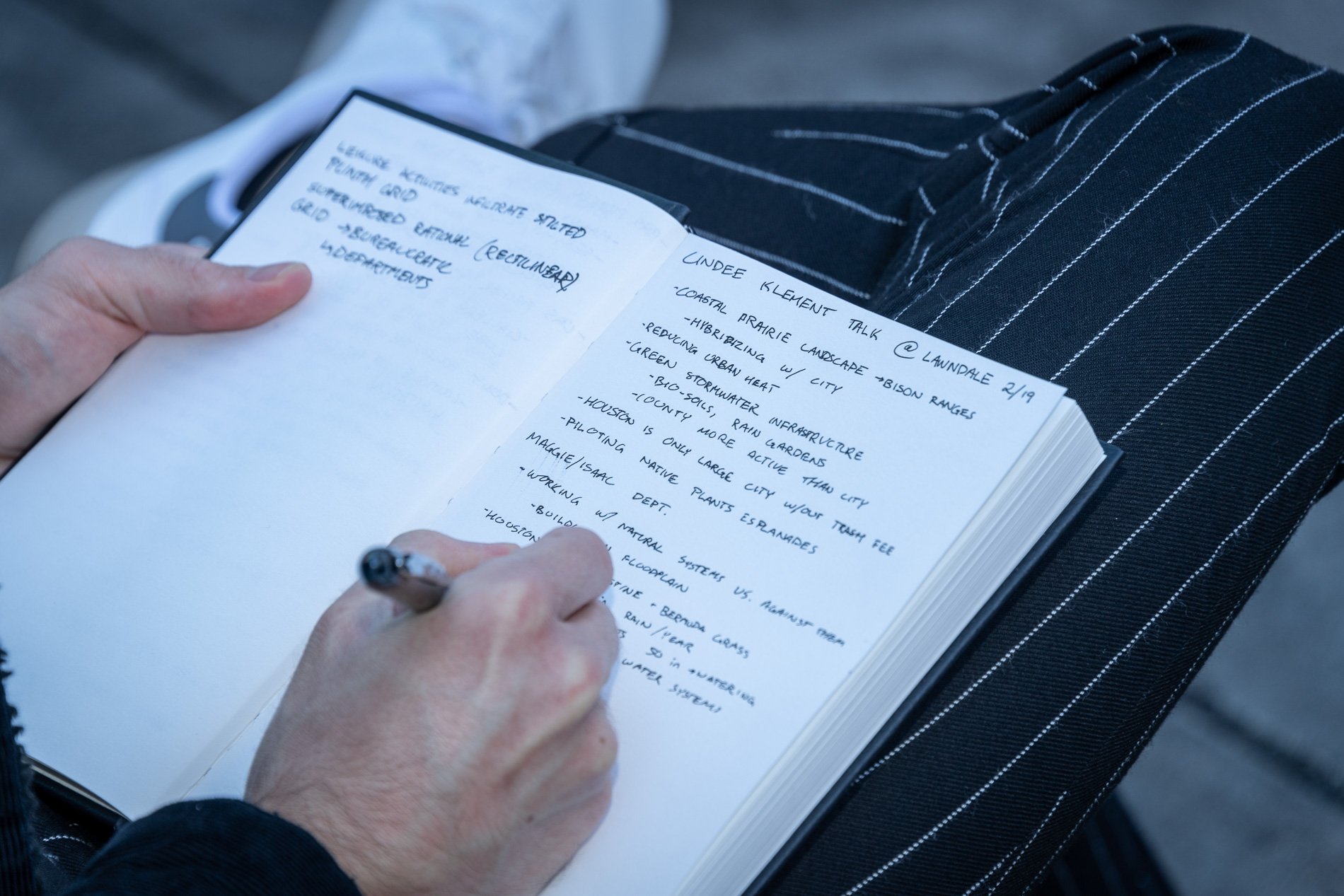

“For profit is the fuel that will change society's landscape practices to embrace the planet's ecological systems in Houston. Applying economics and industrial concepts to my work, I see ecotourism as an untapped resource that can strengthen our environmental and economic health. I propose nurturing and marketing Houston’s ecotourism, through a Symbiosis Celebration of migration, that ultimately encourages and celebrates new mutualistic relationships between Houstonians and the planet. Through fostering relationships that regenerate Houston's micro-ecosystems, we will move our reputation from Chemical Plants to Native Plants — we can prosper as the Green Energy City.” — cindee travis klement

“If you dig deep and keep peeling the onion, artists and freelance writers are the leaders in society - the people who start to get new ideas out.” — Allan Savory

In April 2021, I installed the first native plants in Symbiosis, in Lawndale's Mary E. Bawden Sculpture Garden. Within two months, Symbiosis exploded with bountiful native blooms. Plants expected by the Ladybird Wildflower website to be one to three feet tall in Symbiosis were instead two to four feet tall. In June, the endangered native bees started returning. In the first twelve months, I have witnessed seventy new species in the space: from bird nest fungus to Red Admirals, Monarchs and skippers, skimmers, one of the bumblebees listed as endangered, Bombus pensylvanicus, treefrogs, toads and birds.

Building Mutual Symbiotic Relationships to Power Ecological Recovery

In preparation for the celebration I envision cultivating relationships among the City of Houston, local property owners, Houston's indigenous landscape and its wildlife, soil and climate, food, restaurant, music, visual and performing arts, museums and professional sports team communities.

The following steps will contribute to building these relationships:

· The business and private property owners will need to redirect their existing landscape budgets to native plants that support our wildlife.

· These new landscape practice guidelines will align with the Mayor's Office of Sustainability and Resilience.

· New native wildflower and grass landscapes will slow rainwater, allowing it to soak in and return to the aquifer to cool the planet while sequestering carbon and storing it in the ground where it is stable, providing food and safe habitats for our indigenous wildlife.

· The approximately six hundred species of birds, four hundred and thirty species of butterflies, eight hundred species of Texas native bees, one thousand species of moths, eighteen species of dragonflies, thirty species of turtles, including two box turtles, and seventy-two species of amphibians native to Texas will expand their populations in our city.

· Houston's creatives in the food, restaurant, music, visual and performing arts, museums and professional sports industries will respond to the new mutualistic/symbiotic relationships among Houston's landowners and our unique plant and wildlife in exciting creative ways and performances during the celebratory periods.

· The City of Houston will promote, market, and support the above-described new relationships with its services infrastructure, completing the mutualistic relationship that will support Houston's economy and ecosystems.

Why Houston Can Support Ecotourism

Although Symbiosis taught me the speed with which an urban landscape can transform into a wildlife haven, it was not until I was in Fredericksburg that I realized Houston's ecology is an untapped tourist economy. When you combine Houston's rich soil, high humidity, heat and long growing seasons with the indigenous native plant landscapes supported by Houston's urban irrigated commercial and park landscapes, Houston's native plant wildflower and wildlife tourism can far exceed those of the small towns in Central Texas. Another tremendous asset is Houston's central geographic location in the bird and butterfly migration paths between the North and South American continents and our proximity to the Gulf Coast. Texas has the most butterfly species of any state in the United States. Houston's inner city is 600 square miles; our "sprawl" is an asset to urban ecotourism.

As additional support that Houston can be an ecotourism powerhouse, I have read that one of New York City's most popular tourist attractions is The High Line's native landscaping. In North Texas, Plano also uses wildflowers and music to attract tourism dollars.

Funding

I see businesses and organizations all over the city which are starting to take advantage of the ecological benefits of native landscapes. Unfortunately, many other property owners (business and home) are unaware of the economic and environmental benefits of native plant landscaping. They spend $50-$100 per hour for weekly maintenance and $4—$12 per square foot for seasonal plantings, while also incurring high water usage and bills. Suppose the City appeals to these businesses and individuals to convert their existing non-ecological landscape budgets to native wildflower and grass landscapes. In that case, the City can promote a native plant/wildflower and wildlife, food, arts and music festival that will symbiotically support native ecological systems. The supporting businesses can profit from the tourism they generate.

The Texas Can-Do Spirit

Systems thinking to mitigate climate through industry and the arts is a new territory — will Houstonians embrace this new field of thinking? In Texas, that depends on how you ask and present the need. In our recent history, from Katrina to hurricane Harvey, unsolicited Houstonians volunteered to help their neighbors. In 1901, wildcatters discovered Spindletop, drawing people worldwide to build a better life in unknown territory. “Wildcatter” is used to describe one that drills wells in areas not known to be producing fields. The spirit of the wildcatter is deep in our Texas Can-Do Spirit. It is in our nature to embrace a new field of wild.

Why Big Ideas Are Important.

“The climate needs big, public, audacious goals that everyone can contribute to,” he argues. “Cathedrals were not completed in the lifetime of anyone starting them, but communities bought into these projects.” -The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/12/19/climate-change-cathedral-project/